SHLOMO SAND was born in 1946, in a displaced person’s camp in Austria, to Jewish parents; the family later migrated to Palestine. As a young man, Sand came to question his Jewish identity, even that of a “secular Jew.” With this meditative and thoughtful mixture of essay and personal recollection, he articulates the problems at the center of modern Jewish identity.

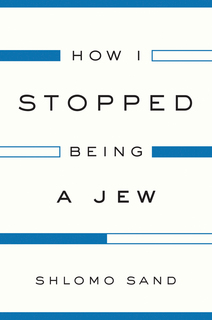

Sand studied history at the University of Tel Aviv and at the École des hautes études en sciences sociales, in Paris. He currently is Emeritus Professor History at the University of Tel Aviv. His books include The Invention of the Jewish People, On the Nation and the Jewish People, L’Illusion du politique: Georges Sorel et le débat intellectuel 1900, Georges Sorel en son temps, Le XXe siècle à l'écran and Les Mots et la terre: les intellectuels en Israël. His current book is How I Stopped Being a Jew.

ABOUT 'How I Stopped Being A Jew' by Professor Shlomo Sand

How I Stopped Being a Jew discusses the negative effects of the Israeli exploitation of the “chosen people” myth and its “holocaust industry.” Sand criticizes the fact that, in the current context, what “Jewish” means is, above all, not being Arab and reflects on the possibility of a secular, non-exclusive Israeli identity, beyond the legends of Zionism.

Extract from 'How I Stopped Being a Jew':

During the first half of the 20th century, my father abandoned Talmudic school, permanently stopped going to synagogue, and regularly expressed his aversion to rabbis. At this point in my own life, in the early 21st century, I feel in turn a moral obligation to break definitively with tribal Judeocentrism. I am today fully conscious of having never been a genuinely secular Jew, understanding that such an imaginary characteristic lacks any specific basis or cultural perspective, and that its existence is based on a hollow and ethnocentric view of the world. Earlier I mistakenly believed that the Yiddish culture of the family I grew up in was the embodiment of Jewish culture. A little later, inspired by Bernard Lazare, Mordechai Anielewicz, Marcel Rayman and Marek Edelman – who all fought antisemitism, nazism and Stalinism without adopting an ethnocentric view – I identified as part of an oppressed and rejected minority. In the company, so to speak, of the socialist leader Léon Blum, the poet Julian Tuwim and many others, I stubbornly remained a Jew who had accepted this identity on account of persecutions and murderers, crimes and their victims.

Now, having painfully become aware that I have undergone an adherence to Israel, been assimilated by law into a fictitious ethnos of persecutors and their supporters, and have appeared in the world as one of the exclusive club of the elect and their acolytes, I wish to resign and cease considering myself a Jew.

Although the state of Israel is not disposed to transform my official nationality from “Jew” to “Israeli”, I dare to hope that kindly philosemites, committed Zionists and exalted anti-Zionists, all of them so often nourished on essentialist conceptions, will respect my desire and cease to catalogue me as a Jew. As a matter of fact, what they think matters little to me, and still less what the remaining antisemitic idiots think. In the light of the historic tragedies of the 20th century, I am determined no longer to be a small minority in an exclusive club that others have neither the possibility nor the qualifications to join.

By my refusal to be a Jew, I represent a species in the course of disappearing. I know that by insisting that only my historical past was Jewish, while my everyday present (for better or worse) is Israeli, and finally that my future and that of my children (at least the future I wish for) must be guided by universal, open and generous principles, I run counter to the dominant fashion, which is oriented towards ethnocentrism.

As a historian of the modern age, I put forward the hypothesis that the cultural distance between my great-grandson and me will be as great or greater than that separating me from my own great-grandfather. All the better! I have the misfortune of living now among too many people who believe their descendants will resemble them in all respects, because for them peoples are eternal – a fortiori a race-people such as the Jews.

I am aware of living in one of the most racist societies in the western world. Racism is present to some degree everywhere, but in Israel it exists deep within the spirit of the laws. It is taught in schools and colleges, spread in the media, and above all and most dreadful, in Israel the racists do not know what they are doing and, because of this, feel in no way obliged to apologise. This absence of a need for self-justification has made Israel a particularly prized reference point for many movements of the far right throughout the world, movements whose past history of antisemitism is only too well known.

To live in such a society has become increasingly intolerable to me, but I must also admit that it is no less difficult to make my home elsewhere. I am myself a part of the cultural, linguistic and even conceptual production of the Zionist enterprise, and I cannot undo this. By my everyday life and my basic culture I am an Israeli. I am not especially proud of this, just as I have no reason to take pride in being a man with brown eyes and of average height. I am often even ashamed of Israel, particularly when I witness evidence of its cruel military colonisation, with its weak and defenceless victims who are not part of the “chosen people”.

Earlier in my life I had a fleeting utopian dream that a Palestinian Israeli should feel as much at home in Tel Aviv as a Jewish American does in New York. I struggled and sought for the civil life of a Muslim Israeli in Jerusalem to be similar to that of the Jewish French person whose home is in Paris. I wanted Israeli children of Christian African immigrants to be treated as the British children of immigrants from the Indian subcontinent are in London. I hoped with all my heart that all Israeli children would be educated together in the same schools. Today I know that my dream is outrageously demanding, that my demands are exaggerated and impertinent, that the very fact of formulating them is viewed by Zionists and their supporters as an attack on the Jewish character of the state of Israel, and thus as antisemitism.

However, strange as it may seem, and in contrast to the locked-in character of secular Jewish identity, treating Israeli identity as politico-cultural rather than “ethnic” does appear to offer the potential for achieving an open and inclusive identity. According to the law, in fact, it is possible to be an Israeli citizen without being a secular “ethnic” Jew, to participate in its “supra-culture” while preserving one’s “infra-culture”, to speak the hegemonic language and cultivate in parallel another language, to maintain varied ways of life and fuse different ones together. To consolidate this republican political potential, it would be necessary, of course, to have long abandoned tribal hermeticism, to learn to respect the Other and welcome him or her as an equal, and to change the constitutional laws of Israel to make them compatible with democratic principles.

Most important, if it has been momentarily forgotten: before we put forward ideas on changing Israel’s identity policy, we must first free ourselves from the accursed and interminable occupation that is leading us on the road to hell. In fact, our relation to those who are second-class citizens of Israel is inextricably bound up with our relation to those who live in immense distress at the bottom of the chain of the Zionist rescue operation. That oppressed population, which has lived under the occupation for close to 50 years, deprived of political and civil rights, on land that the “state of the Jews” considers its own, remains abandoned and ignored by international politics. I recognise today that my dream of an end to the occupation and the creation of a confederation between two republics, Israeli and Palestinian, was a chimera that underestimated the balance of forces between the two parties.

Increasingly it appears to be already too late; all seems already lost, and any serious approach to a political solution is deadlocked. Israel has grown used to this, and is unable to rid itself of its colonial domination over another people. The world outside, unfortunately, does not do what is needed either. Its remorse and bad conscience prevent it from convincing Israel to withdraw to the 1948 frontiers. Nor is Israel ready to annex the occupied territories officially, as it would then have to grant equal citizenship to the occupied population and, by that fact alone, transform itself into a binational state. It’s rather like the mythological serpent that swallowed too big a victim, but prefers to choke rather than to abandon it.

Does this mean I, too, must abandon hope? I inhabit a deep contradiction. I feel like an exile in the face of the growing Jewish ethnicisation that surrounds me, while at the same time the language in which I speak, write and dream is overwhelmingly Hebrew. When I find myself abroad, I feel nostalgia for this language, the vehicle of my emotions and thoughts. When I am far from Israel, I see my street corner in Tel Aviv and look forward to the moment I can return to it. I do not go to synagogues to dissipate this nostalgia, because they pray there in a language that is not mine, and the people I meet there have absolutely no interest in understanding what being Israeli means for me.

In London it is the universities and their students of both sexes, not the Talmudic schools (where there are no female students), that remind me of the campus where I work. In New York it is the Manhattan cafes, not the Brooklyn enclaves, that invite and attract me, like those of Tel Aviv. And when I visit the teeming Paris bookstores, what comes to my mind is the Hebrew book week organised each year in Israel, not the sacred literature of my ancestors.

My deep attachment to the place serves only to fuel the pessimism I feel towards it. And so I often plunge into despondency about the present and fear for the future. I am tired, and feel that the last leaves of reason are falling from our tree of political action, leaving us barren in the face of the caprices of the sleepwalking sorcerers of the tribe. But I cannot allow myself to be completely fatalistic. I dare to believe that if humanity succeeded in emerging from the 20th century without a nuclear war, everything is possible, even in the Middle East. We should remember the words of Theodor Herzl, the dreamer responsible for the fact that I am an Israeli: “If you will it, it is no legend.”

As a scion of the persecuted who emerged from the European hell of the 1940s without having abandoned the hope of a better life, I did not receive permission from the frightened archangel of history to abdicate and despair. Which is why, in order to hasten a different tomorrow, and whatever my detractors say, I shall continue to write.