Revolutionary Silhouettes

by Kevin Annett

Revolutionary Silhouettes

by Kevin Annett

Vancouver: May, 1974

I had just turned eighteen when I met Jack Thompson. He worked as the grounds keeper of Woodland Park, where on that particular day, a big labor protest rally was in full swing. Something about the old man caught my attention, as he shuffled about his duties, seemingly unmindful of the raucous speeches and cheering.

One of my buddies from the postal workers union noticed me staring at the senior, and he said with a smile,

“You wouldn’t know it, but old Jack over there was a real hellraiser in his day. The Winnipeg General Strike, the On to Ottawa Trek, you name it, he was in the thick of it.”

It was the springtime of my devotion, and my first seeds of political awareness longed to be watered. After my next trip to the john, I approached Jack, who was emptying out a trash can.

“You seen one of these?” I asked him, extending a leaflet about the purpose of our rally, which was to oppose the Trudeau government’s wage controls program.

Jack snorted.

“That means jack shit,” he pronounced, tossing a garbage bag into his pushcart. “That’s no way to stop the bastards.”

Jack had sharp, crystal-clear eyes that belied his general shoddy appearance. His expression breathed wisdom and experience beyond my ken. And he could see that I was hungry to learn.

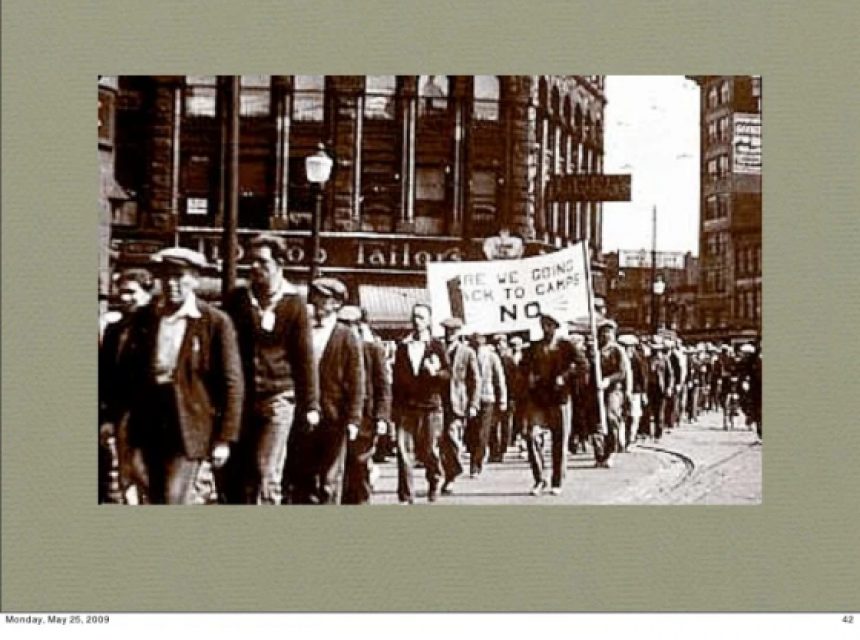

Jack had immigrated from the slums of Birmingham when he was a boy, and worked at every shitty job imaginable across Canada. By the time he was my age, he had been repeatedly beaten, jailed, and blacklisted for union organizing. Under a false name, he was hired as a railway mechanic in Winnipeg just in time to join 40,000 other workers in the General Strike in the summer of 1919.

“They talk now of it being about union recognition and wage hikes, and sure it was, but that sure as hell wasn’t all,” Jack recounted later, when we took to sharing beers at the Waldorf on east Hastings.

“Revolution was in the air, brother, and not just because of Russia and the Bolsheviks. All them war vets wanted something to show for all them arms and eyes they’d lost. We all knew the bosses had to go. But only a few of us knew how to make it happen.”

All the Reds who I knew up to then were bland, scholarly types who could tell you the intricacies of Marxist economics, but didn’t know their ass from a soldering iron, and had pablum for guts. Jack was genuine. He bore the personal scars that showed how the system wasn’t meant to serve anyone but the ruthless and the rich. And he had lost not an ounce of his radical resolve over nearly sixty years.

“The trouble nowadays is people got too much fat on them, they expect everything nice and easy. In the Wobblies, we used to say, you can’t skin capitalism claw by claw, you gotta kill the whole beast. But easy times makes people forget what it is they’re up against.”

Jack had been married once, but she had left him many years before. He was childless, friendless, and alone. But regret and loneliness didn’t seem to mar him. He was a rock-ribbed realist.

“If you take on the system and don’t ever stop, you can’t expect bouquets or a pension from it,” he reflected. “I’m seventy-four now, and on minimum wage. I got nothing much to show for all them years of struggle, just the satisfaction of doing what I had to do. Nobody wants to remember the real revolutionaries, son, they’re too scared of us. We’re always a permanent kind of threat. That’s why nobody ever comes around to ask me of those times, not even the so-called lefties.”

“But I’m asking,” I replied. And during the times we had together, I drew from Jack’s living well some of the inspiration that would lead me on my own good red road.

I only learned later how prominent Jack Thompson had been in Canada’s radical labor movement, and in winning the great victories that have fed so many, and on whose shoulders we unrepentant insurgents stand. He had lived his life only for others, and for the highest ideal of an emancipated humanity. And yet every night he sat alone in his cramped apartment on the Woodland Park grounds at his still-glowing fire so rich with memory and purpose, as the world stumbled on in its unchanging banality of official murder and madness.

I think of Jack Thompson more these days, as another half century has come and gone. Old age ambushed both of us with the realization that all we are left with at the end is our own fiber, and the love we have demonstrated in the radiant battles that we lost and won, that have fed the next generations.

Jack died three years later, alone but still remembered by a faithful few. On his headstone is emblazoned a hammer and sickle, with the inscription,

“An injury to one is an injury to all. Workers of the world, arise.”

--