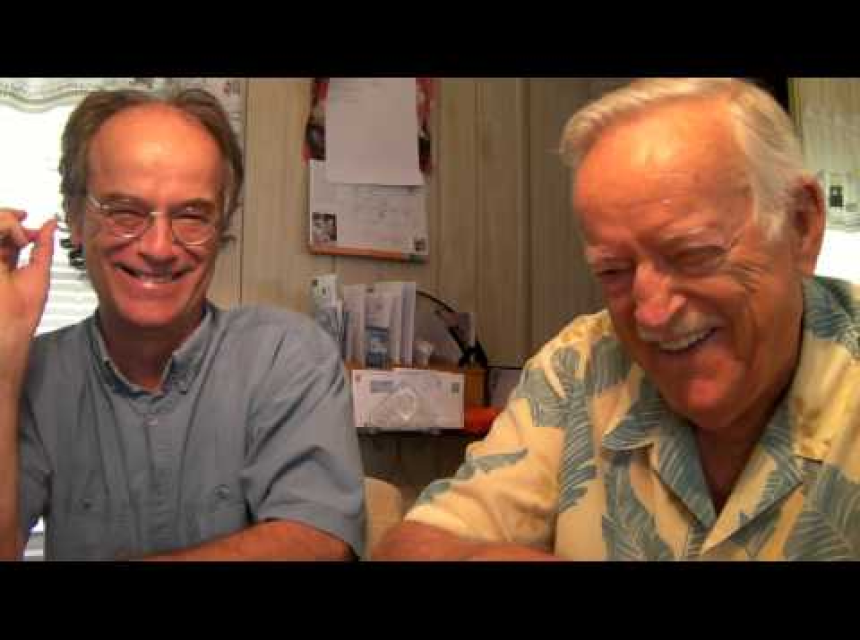

Loving what we know: William and me

by Kevin D. Annett

â

Loving what we know: William and me

by Kevin D. Annett

Wandering into the outback of one's sixties invariably leaves me, at least, with a persisting sense of exile. Perhaps I'm not alone, if the strained and semi-confused demeanor of other folks my age means anything. The lot of us came of age during the 1960's, after all, when the tyrants were toppling; so today's droll, narcissistic nuthouse that passes for Civilization is doing its damnedest to bludgeon our dreams into early retirement.

My father Bill is nearly ninety, although you wouldn't know it. He's just published a sheaf of his writings over seventy years called Letters from my Gin Mill: An Octogenarian Odyssey (Amazon, 2017) which brims with his usual slashing wit and levity, undiminished by all the wear and tear.

Perusing his fifty selections, it struck me how the sense of exile runs like a vein through anyone who sifts through the strata of their own life with something more than remembrance. Whether situated in the dust-bowl prairies that he knew as a child or in the surreal world of high finance, Dad's stories echo a sort of heart filled longing for that which he never found during his own kick at the can.

Dad's a Yankee who ended up in Canada at a tender age about the same time that Wall Street went under. Now he's returned to the Land of the Fee to live out his final time in a Daytona Beach flat with his little dog Princess. And so while not strictly an expatriate, Bill Annett seems to be in that set-apart zone reserved for the artist who is looking for summation. He's still got a lot to teach me, especially about accepting ourselves.

I find myself digressing more with the passing years, which comes I suppose from lots of memories and battle hardedness as well as possible early onset dementia. I recall scenes from my own child hood more vividly these days, especially concerning my Dad and my mother Marg. They couldn't have been more different.

As kids, some unspoken pneuma wafts us in the direction of one parent or the other. In my case it was towards Dad, which of course frustrated Marg to no end. One reason I viscerally identified with my father was because he saw bullshit for what it was, in the crowd or in himself. He had an innate self-acceptance that didn't require that he thirst after other peoples' approval. I guess you could call him the ultimate realist. Marg of course was the polar opposite.

I can't say I wasn't touched by mother at all, for although I wasn't strictly birthed by her but lifted, or hijacked perhaps, out of her sliced belly, Marg left some of her mark on me. In my early years I hankered after some great achievement, a stunning public recognition that would give me the friendship and love that always seemed to elude me. But more than that – and here's where Dad came in – I too saw through the oceans of crap around me. And yet unlike Dad I had a burning need to do something about it all. I was permanently restless, and already as a teenager in exile from the need to fit in somewhere. I was compelled to do something new, and so I could already sense the impending long loneliness that would be my life.

Unlike my mother, Dad always accepted me, which to a son is like oxygen. He and I would go years without speaking, but I knew he was out there somewhere rooting for me. Now it's different, and when we meet up we're like two guys batching it together and swilling our thoughts around the ways war vets do with their vodka and tonics. Being with Dad has been like a home coming in a way, or maybe an oasis.

At the end of the day I love my father not only for who he is and what he's given me but for that peculiar Annett gift of exposition and clear sightedness that I've inherited from him. And knowing who we are and loving what we know is at least one of the better qualities of the true man.

In one of his recollections of his deceased brother Ron, Dad writes of their deathbed farewell:

"By the time I reached Florida three or four days later, he had already told them to pull the plug. I found I had no tears left, nor regrets over a brother who never made the headlines but in some strange way for me will always be one of the true riders in the chariot."

And so too my father.

........................................

Order Letters from My Gin Mill: An Octogenarian Odyssey by William Annett through Amazon