Confessions of an Allegedly Angry Man: Breaking the Awful News

by Kevin Annett

Confessions of an Allegedly Angry Man: Breaking the Awful News

by Kevin Annett

“In times like the present, men should utter nothing for which they would not willingly be responsible through time and eternity.” - Abraham Lincoln, 1861

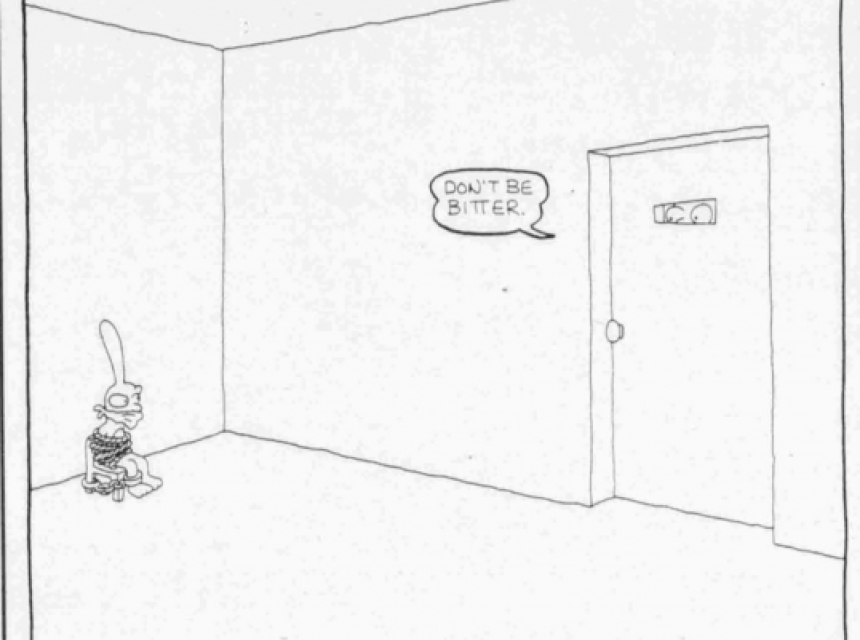

The other day one of my less than insightful readers whom I'll call Shirley took offense at something I wrote. With a passion unusual for a pale Canadian, Shirley explained to me how I would have much more support from the public if I wasn't so "bitter and angry" about my own country, and learned instead to "look for the positive in people". She also mentioned something about God.

Shirley's fervent accusation perplexed me at first, since the dire writing to which she referred was composed by yours truly as a satirical poke at Canadians' moribund capacity to strain out a gnat while swallowing a camel: in this case, the latter being our sordid Group Crime and Denial involving lots and lots of dead brown children. After all, one can only laugh at enormous tragedy, since it defies all of our words.

In fact the woman's barbed censure of me came at a fitting moment, since not even an hour before her remarks I had been asked by an interviewer to do more than comment on the murder of the nine year old girl named Vicky Stewart. My interlocutor asked me how her death made me feel. And the truth was that I didn't feel anything.

I've sometimes imagined what position in life I'd enjoy if I was actually the nefarious man portrayed by my critics. I'd be a lot wealthier, for one thing. In Shirley's case, if I indeed harbored the kind of bitter rage she's detected in me from her remote vantage point, then I would be exploding passionately over Vicky's beating to death by a United Church matron named Ann Knizky. If only I had such rage! But worse the luck, I'm too much of a Canadian to not glance over my shoulder with concern at how the crowd might interpret my blast of indignation. For as any of us know who have faced the fire of official vilification, in our country the problem is never that a wrong is done – it's that someone is talking about it. Just ask Shirley.

Vacuous critics aside, I've spent today probing my absence of feeling concerning little Vicky's killing. I've seen her picture and come to know her sister Beryl who witnessed the fatal blow. I know the details of Vicky's brutal ending as well as I do the untold thousands of other faceless victims whose extermination I have chronicled and shared with a disbelieving world. And perhaps that fact explains the thick padding around my heart and the staunched tears that cannot flow. No doubt too the grief of having my own beloved daughters stripped from me when they were mere infants has helped to exile me into this emotional dead zone where my rage cannot find its voice. In that way I'm a lot like my pale country men and women. For like the classical Greek heroine Antigone, if I have died it is so that I may truly help the dead: my fellow Canadians.

Besides a failing agility and subsiding libido, entrance into my sixties has brought me an unexpected clarity about what I've actually been doing these past two decades. I thought for a long time it was to expose a terrible wrong called genocide in my own backyard and give voice to its stumbling survivors. As it turns out, that was all but a preamble to the main event.

Nobody ever likes to have the awful truth presented to them, particularly when their end is in sight. For instance, soon after I was ordained as a clergyman I was called to the bedside of a dying woman named Carol who was the young mother of three children. She had barely days to live. Her parents and brothers were all there along with her distraught husband. None of them wanted to face the truth that she was about to die. They tried cheering her up and told her she'd be up and better soon. But she knew the truth, just as they did, somewhere beneath their dread and denial.

As Carol got worse and began to sink into a coma, I finally said gently to everyone in the room, "Now might be a good time for all of you to say goodbye to Carol."

They all turned to me in shock. Carol's mother barked at me angrily, "How dare you!"

"She doesn't have much time left" I replied, but the woman couldn't hear me.

The mother never did say goodbye to her daughter; instead she stormed out of the hospital room. But eventually everyone who remained faced the truth, and that's when their tears and sobbing began, and their goodbyes to their dying Carol. Yet none of the bereaved family ever spoke to me again, avoiding me with hostile glances as if I had been the cause of her death.

Equally apropos is another story much like that one, told by a survivor of a Nazi death camp. The man was a Polish doctor being shipped in a cattle car to Auschwitz with hundreds of children and their parents and teachers. As the train neared the death camp, one of the elders, an old woman who'd taught music in the Cracow ghetto from where they had been shipped, began to tell the children happy stories of the beautiful land of eternal youth that awaited them all. She began to lead them in singing. Soon the children were all calm and contented, even as the blaring sirens and screams of Auschwitz approached.

The surviving doctor remembers that he grew angry at the old woman and took her aside.

"Why are you telling these children such lies, at a time like this?" he demanded.

The old woman smiled sadly and replied,

"This is not the time for the truth."

Part of me agrees with the old woman: the childish part of me that once felt that love means medicating the suffering with a narcotic called hugs and happy wishes. But my seasoned and higher self understands that the truth is never dispensable, especially at moments of suffering; and that any love that denies the truth is as false and transitory as a mild painkiller. Only the truth can allow us to grow beyond our infantile need for protection and mature past the wheel of injustice. For experience shows us that the universe does not want us to be happy as much as it wants us to grow up.

People like Canadians - whose culture has the blood of the innocent on its hands and who are caught in an enormous group lie required by their crime - are not capable of growing up. Like any bully caught with the club still in his hand, white Canadians are not moved or concerned by the legions of children who were tortured to death by their churches as much as by someone who points out the bodies. As a senior United Church official once exclaimed at me, "We know all about those things. The only problem is that you're talking about it."

The official's words are a perfect depiction of the banality of institutionalized evil: of the fact that those immersed in a Group Crime are not so much intentionally evil as they are dead in their hearts and dissociated from their own feelings. This obtuse condition was epitomized by the Anglican clergyman who confronted some of us who were leafleting his cowed parishioners about the more than 50,000 children who died at their corporate hands. The man screamed at us,

"We've said we're sorry! What more do those people want?"

And the pastor was genuinely shocked and confused when I replied,

"Imagine if it was your child who was raped, killed and shoved in the ground somewhere. What would you want?"

My question confused the man only because the whole "issue" of his groups' complicity in mass murder in his own backyard had never been internalized by him, or by his group. Raped and murdered children was not a reality to him but an abstraction, unrelated to his daily life. And it is precisely that kind of numbed and hermetically sealed moral capacity that is required for any Group Crime to go unresolved and unpunished, and thereby continue. The greater the atrocity, the greater the denial and personal distancing of it, whether at Auschwitz or the Alberni Indian residential school.

Passion and anger has no place in the rigid mental dissociation of group criminals like Canadians, for such upheavals threaten to crack open the careful arrangement of make believe humanity and personal self-exculpation that characterizes the winners of any war of genocide. Ultimately this neurosis explains the behaviour of my antagonist Shirley who took such offense at my laughing at the denial and delusions of my people. For to a white Christian in Canada there is no greater offense than to cause a controversy or division. Clearly, they don't read their own Bible very much.

At the end of the day, our real enemy is not the risk of breaking glass in outrage but our incapacity to do so. Our frozen feelings and captivity in an arrangement of death and lies is as much a threat to the fiber and being of the Anglican clergyman as it is to you and me. Genocide condemns the killer and the killed alike. The one who tortures another to death and "gets away with it" carries around a death sentence and is eventually destroyed from within. White Canada, languishing in its group lie of "healing and reconciliation", is dying from the inside out because it has yet to face itself.

I have no prescription for the terminal condition of my people because there is no cure. As much as Canadians deny their own condition, there will eventually come the fact of death. It is not to the passing crime called Christian Canada that we must minister, but to those who will come after it: the next generations, whether native or white, who must know the whole truth lest they replicate the evil.

Perhaps one day I will learn to let my own blocked grief flow and find that voice of rage that will shatter the prison bars. But if such grace falls upon me or on any Canadian it will be because of and not despite our relentless facing of the truth and our struggle to speak it. For as Alice Miller reminds us,

"The truth about our childhood is stored up in our body, and although we can repress it, we can never alter it. Our intellect can be deceived, our feelings manipulated, and conceptions confused, and our body tricked with medication. But someday our body will present its bill, for it is as incorruptible as a child, who, still whole in spirit, will accept no compromises or excuses, and it will not stop tormenting us until we stop evading the truth."